MILD ALE:

A Rant, History & Wish

Everything I've learned about Mild Ale I've learned from Ron Pattinson's blog, Shut Up About Barclay Perkins. For a while I was obsessed with Mild because it is an enigma to modern brewers... whether they realize it or not. Here is what the BJCP Guidelines say about Mild:

13A. Dark Mild

Overall Impression: A dark, low-gravity, malt-focused

British session ale readily suited to drinking in quantity.

Refreshing, yet flavorful for its strength, with a wide range of

dark malt or dark sugar expression.

Comments: Most are low-gravity session beers around 3.2%,

although some versions may be made in the stronger (4%+)

range for export, festivals, seasonal or special occasions.

Generally served on cask; session-strength bottled versions

don’t often travel well. A wide range of interpretations are

possible. Pale (medium amber to light brown) versions exist,

but these are even more rare than dark milds; these guidelines

only describe the modern dark version.

Well, at least they now acknowledge that they are only describing modern versions. That wasn't always so. Earlier, and not that many style guideline versions ago, the BJCP read thus:

History: May have evolved as one of the elements of early porters. In modern terms, the name “mild” refers to the relative lack of hop bitterness (i.e., less hoppy than a pale ale, and not so strong). Originally, the “mildness” may have referred to the fact that this beer was young and did not yet have the moderate sourness that aged batches had. Somewhat rare in England, good versions may still be found in the Midlands around Birmingham.

Comments: Most are low-gravity session beers in the range 3.1-3.8%, although some versions may be made in the stronger (4%+) range for export, festivals, seasonal and/or special occasions. Generally served on cask; session-strength bottled versions don’t often travel well. A wide range of interpretations are possible.

"evolved as one of the elements of early porters"?! Thankfully they've corrected that bogus statement but considering how long this fallacy was left to sit and fester it's no wonder today's homebrewers have little or no knowledge of what a Mild Ale actually is... or was. And why does the BJCP list Mild only in the Brown British Beer category? You will get a tad closer to the truth of Mild if you read the Brewers Association guidelines:

- English-Style Pale Mild Ale

- Color: Light amber to medium amber

- Clarity: Chill haze is acceptable at low temperatures

- Perceived Malt Aroma & Flavor: Malt flavor and aroma dominate the flavor profile

- Perceived Hop Aroma & Flavor: Very low to low

- Perceived Bitterness: Very low to low

- Fermentation Characteristics: Diacetyl is usually absent in these beers but may be present at very low levels. Fruity esters are very low to medium-low.

- Original Gravity (°Plato) 1.03-1.036 (7.6-9 °Plato)

- Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (°Plato) 1.004-1.008 (1-2.1 °Plato)

- Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 2.70%-3.40% (3.40%-4.40%)

- Bitterness (IBU) 10-20

- Color SRM (EBC) 6-9(12-18 EBC)

- Body: Low to medium-low

- Here at least the BA recognizes both Dark Mild and Pale Mild. There are still data points that are not historically correct.

Let's start with the name "Mild". Brewers today interpret the name to mean mild in character... low bitterness, low ABV low body. When in truth the term "mild" in the 1800's, when Mild Ale was developed and became a top selling beer in England, "mild" meant "young" or "fresh". Any and all beer that was sold young was described as "mild".

You had mild Pale Ales, mild Porters and so on. Mild wasn't considered a style, it was a description of condition. These descriptions were held from the 1700's right up to the 1940's.

By the early 1800's English brewers began using a shorthand to label their product. (Named beers were a rarity) Mild Ales were designated using the X system. In general, the more X's the higher the gravity of the beer. For example, an 1830's X would have a gravity of 1.070. That's higher than a Pale Ale of the same era. For comparison an XX gravity would average 1.085 and XXX clocked in at 1.100!

Hop bitterness too was much higher than you will find in a modern Mild Ale. A quick look at the 1830 to 1880 recipes I have on hand and the calculated IBU's run from 57 IBU to over 100 IBU. And then there is the color. Most all Mild Ales of this time were brewed with 100% Pale Malt. The color hovered right around 6 SRM to 7 SRM. Even in the early 20th century when Mild began to get darker the color was closer to what we now call amber at 12 SRM to 15 SRM.

By around the 1860's English brewers began to include adjuncts or specialty malts into the grist of Mild Ales. Invert sugar was popular as was Brown and Mild Malt. When the darker versions began evolving a touch of Black Malt is sometimes found.

Pale Mild Ale began to change coinciding with World War I. Grain and sugar supplies were diverted to the troops. Brewers were faced with shortages and rationing. Mild Ale fell from a base OG of 1.070 to 1.050. They would briefly tick up in between the wars but by World War II is when Mild Ale slipped to a paltry 1.030 or lower. After that war they began to regain some of their gravity but not by much.

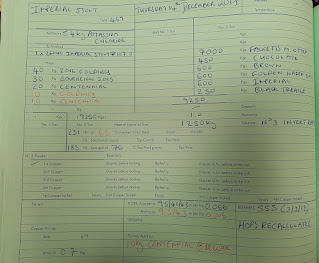

Here is one the last respectable Mild Ales brewed right at the beginning of WW I.

(scaled to a 5 gallon/19 liter homebrew batch)Courage Brewery, London - 1914 X Ale- pale malt 9.75 lb 82.28%

- crystal malt 60 L 0.75 lb 6.33%

- black malt 0.10 lb 0.84%

- No. 3 invert sugar 1.25 lb 10.55%

- Fuggle s 120 mins 0.75 oz

- Fuggle 60 mins 0.75 oz

- Hallertau 30 mins 0.75 oz

OG 1055

ABV 5.29

IBU 26

SRM 15.5

(source:

Shut Up About Barclay Perkins)

The Mild Ale we know today only began to show up regularly in the 1930's. Not as old as you thought eh?

By the 1950's nearly all Mild Ales were dark with only a rare outlier showing up on the pale end of the scale. And then sadly, they were gone completely by the end of the 1970's.

Mild may have slipped away altogether if it weren't for the homebrew and craft beer explosion in the 1980's and early 1990's. Even then, it was the homebrewer looking for something different and "new" who revived this almost lost beer. Craft brewers were more enamored with bringing back another style from the brink of extinction, the IPA. But that's another story. The problem was that very few brewers by this time actually knew the history of the

style and so relied on the few publications available that mentioned "mild". How were they to know that Mild Ale was not always dark? That it was not always low in ABV or bitterness?

If I had some influence on the BJCP and other publishers of beer style guidelines I would urge them create a sub category to encompass the history and tradition of Mild. London behemoth brewer Barclay Perkins attempted to satisfy all versions in the 1930's by producing five or more variations of their X and XX Ale. There was a pale X and XX. One of each that was colored up after fermentation to appease those who preferred the darker kind. (same beer just some color added) Another version was X and XX colored darker and sweetened.

If we can have pastry stouts and hazy IPA's I believe there is room for a pale, strong, and hoppy Mild Ale. Don't you?